Medium: Toy and game

Stuff that shouldn’t need to be discovered

I have been researching since some time now, about learning from play. I came from a personal learning experience I had in design, by playing Lego, and from FL Studio, that was other toy to me. In the beginning, it appeared to me that these platforms offered to the player a ramp, where the user instead of having to climb a wall of difficulty into a discipline, would be able to enter smoothly. Soon I started discovering that there was a lot more to it.

I ran into Salen & Zimmerman’s Rules of Play book. I remember when I opened it, it displayed this diagram of enter, play, stay. Instantly the idea of learning was a lot more complex than just putting a ramp into knowledge: no matter how well built a learning curve is, the learning experience can still be boring. The idea of applying game design theory into learning, would merge both, and make learning an accident. At this point, I thought that it was an original idea, and perhaps, there were other ways of engaging people into the stay learning other than play. Another idea that prove wrong:

Apparently, playing and learning are intrinsically related. Separating them has brought us the same kind of misconceptions that separating memory from intelligence; and for a fact, my own school put an enormous effort on the memorizing part of teaching, but none in the play part of it whatsoever. Many years from that moment, (I still get angry, but also) I realize that instead of discovering something new, I was just un-learning a misconception, that now I know, a lot of people have already unlearnt; and there is a sort of cultural campaign going on where we want to start understanding the education in a better way. It is a big step, but I believe that after this step, there are many other steps to follow.

Two kinds of learning, two kinds of play

With the trend of gamification and STEM toys, I have ambivalent opinions, as may happen to anyone that sees an answer to a question he cares. In one side, I really appreciate the idea of STEM toys, thanks to our schooled mindsets, we put too much effort in researching it’s cognitive benefits, but too little into expanding the idea into all the areas out of STEM. I think that Papert, Resnick and others, created a great leap out from our prison-based educational system with an idea where the student drives his learning process. I believe that we still need to put more subjects and approaches than exclusively mindstorms. This is where all the educational play industry came to play: now you can learn languages, math, sciences and everything in a very gamified fashion. Some parents may describe how they saw their children’s eyes sparkling in front of second grade equations, when they were presented in form of a game. These comply with the requisites of enter, play, stay, and therefore they motivate a kid to enter, to play and to keep playing in a game that will be teaching him. What the gamification culture, I believe is lacking, are more steps towards what mindstorm’s was pushing for: a learning process that is driven by the kids, because the difference between a directed learning process and one that is open ended, make the difference between educating to be the perfect employee or a self-driven individual.

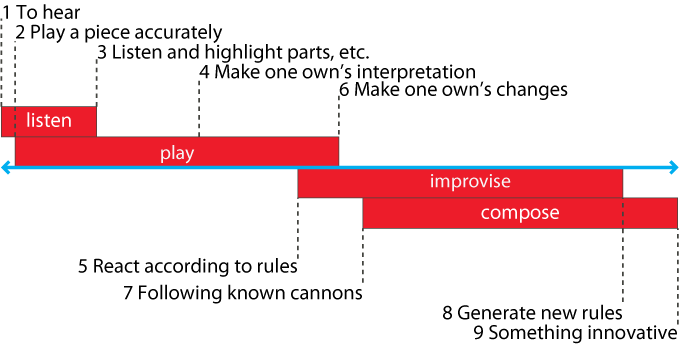

To give a clearer idea, I will explain how I discovered the difference between these two plays. The works I have been doing, have been about music; and one aspect that I foud frustrating, was the fact that for known instruments, people misunderstands learning music with learning to play songs. This made me connect two different ways of understanding music learning with two different ways of playing and later, with two ways of learning:

(From the Brocs thesis)

As you can see, all the way from listening to a song, into creating your song, there are many levels of involvement into the activity. But more than involvement, what I want to put here are different levels of divergence of play: where the musical outcome from playing a song thoroughly is desired to be always similar, the musical outcome of improvising or composing will never be the same. For the case of play, I would place a typical math learning game (where you can win or loose), at the same level as “playing a piece accurately”, which at least, still involves the player more than, say when he has just “listening” to a math class and following exercises. Of course that we won’t expect a game to take players to discover math theorems, but I wonder what happens with all the available spectrum of divergent play that math could possibly offer, besides following a right formula. So, I feel very thrilled when I learn about game concepts like Sim City, Scratch, or Lego; but sadly I haven’t been thrilled any proper theory body for divergent game design. I believe that such a book would also be a bold statement about how to teach humans how to learn, be creative, be effective, and not to loose their uniqueness in the process. I expect recommendations of bibliography on the comments.